Featured image: “The Powerpuff Girls” by OZartwork

I absolutely adore The Powerpuff Girls, Craig McCracken’s cartoon series that ran for six seasons on Cartoon Network starting in 1998.

Because I adore the original, I’ve not had the courage to begin watching the new version. There have been a lot of remakes, reboots, and sequels to things from my youth lately, and most of them have taken something fun, entertaining, and beloved, and turned it into a dreary vehicle for faddish political grandstanding. Disney actually dared to take a live-action dump on Sleeping Beauty, and more recently made a Star Wars sequel; I forget the title, but I think it was something like Ensign Mary Sue Does It Better than Everyone Else in Space, because heaven forbid that the “strong female character” should have any weaknesses or need to grow into her role.

All the press I’ve seen about the new Powerpuff Girls has been bad press. Everyone talking about it is all feminist this and feminist that, as if children’s cartoons should be about identity politics instead of explosions and gross-out jokes. Everyone’s talking like it’s a big deal that the show’s protagonists are female, as if it’s unusual for superheroes to have innies instead of outies.

That’s all nonsense. Superheroines have been around as long as superheroes. The Powerpuff Girls were not unique because they were female, but because they were female and in kindergarten. If you do not understand that, you do not understand The Powerpuff Girls.

Indeed, the early clip of the new version that appeared on YouTube feels less like a freewheeling retro action-comedy (what the original was) and more like a scolding lecture:

Just look how much schoolmarmish finger-wagging they managed to pack into those forty-six seconds: masculine bad, hippie good, you can’t say “princess” for some reason …

Also, Buttercup’s new voice sucks.

I’m highly suspicious of that princess thing in particular, as that has apparently become a feminist shibboleth of late, as witness the YouTube shock video (link NSFW) that made the news a year or so back with little girls in princess outfits screaming cuss-words they probably didn’t understand. Because vulgarity empowers women. Or something.

Somewhere around the same time, I heard an interview on National Public Radio with some guy from Pixar. The NPR talking head, after taking a few hits off his bong to get that signature public radio voice, asked the Pixar dude if he thought it was “problematic” in some way that Pixar made movies about princesses.

The Pixar guy laughed nervously and said by way of reassurance that Pixar made movies about princesses, but it certainly didn’t make movies about, y’know, princesses.

This fascinated me. Neither of these two bothered to define what he meant by the word princess, nor to explain why there’s anything wrong with princesses. It was pure virtue-signaling: the Pixar guy was not actually saying anything meaningful, but merely reassuring the empty suit that he was one of the tribe.

I have not watched a Pixar movie since. If Pixar doesn’t like its own material, why should I? I realize the interviewer probably caught that poor slob by surprise, but what he should have done was boost his product instead of apologize for it. He should have said, “Hell yes we make movies about princesses. We love princesses at Pixar, which is why we make movies about them. Our next movie has ten princesses, and the movie after that will have twenty princesses. We are set to double our princess growth rate every year for the next fifteen years.”

Then I would have run out and bought a Blu-Ray of every Pixar film in existence while shouting, “Suck on this, NPR prudes! What kind of a name for a man is Ira, anyway?”

Getting back to the subject of The Powerpuff Girls, let me just say that the idea of a five-year-old girl getting offended at being called a princess is ridiculous. No little girl gets upset at that unless an adult has coaxed her into it, because getting offended at innocuous words is a grownup hobby, and it’s high time the grownups knocked it off.

Over on Polygon, Allegra Frank, who may or may not be a bluntly worded allergy medication, discusses her history with The Powerpuff Girls, and she has missed the point. She has missed the point so completely that if the point suddenly exploded, she wouldn’t hear the sound for three days.

She claims, “Girl-starring cartoons remain few and far between.” This is an oft-repeated falsehood, though it’s one Frank might actually believe if she’s not paying attention. Presumably, she has never heard of Teen Titans, Winx Club, W.I.T.C.H., Strawberry Shortcake, Dora the Explorer, Legend of Korra, My Little Pony, My Life as a Teenage Robot, Kim Possible—and I did that off the top of my head without looking, and without even pulling out any Japanese titles.

She also, whether she knows it or not, utters what are almost certainly falsehoods about her own childhood:

My kindergarten teacher shuttled the other girls in my class and me to opposite corners away from the boys, encouraging us to play house while they got to destroy their building block skyscrapers.

Baloney. Nobody discourages girls from playing with blocks. More likely, this is something someone taught her in college, and that she projected back onto her childhood. If the teacher separated girls and boys, it was probably a wise move to keep order in the classroom. She could play with them after school or at recess instead.

This misinformation is forgivable, because few if any adults can say they remember kindergarten clearly, but for that very same reason, Frank should refrain from accusing her kindergarten teacher of things she likely didn’t do.

Frank reveals here the sad truth that some people are never satisfied. She claims that the new version of the show is insufficiently feminist, but it’s not as if its creators aren’t trying to pander to her. Here’s from the Huffington Post‘s interview with the crew of the new version:

“One of my favorite things about this journey with the show is, as a woman, how far feminism has come since the last show ended,” said [Haley] Mancini on how she’s approached writing the series.

But the show isn’t a woman, it’s a cartoon. Or did she mean feminism is a woman? Ah, never mind. And again:

The staff behind the new Powerpuff characters felt lucky that feminism is integrated into pop cultural spaces far more than audiences permitted during the run of the original series. “I think girl superheroes were a bit of a novelty then,” said [Bob] Boyle. “Girls are really embracing their geekdom and I think it’s also OK for boys to be into girl superheroes. That whole dynamic has changed from when [the show] first came out.”

As an aside, I’d like to note that only someone with a non-STEM college degree can say “integrated into pop cultural spaces” with a straight face. But besides that, Boyle is either a liar or embarrassingly unfamiliar with the genre he’s working in. This is the co-executive producer of the show, folks, and he doesn’t know that there were girl superheroes before 1998.

An acquaintance recently told me that he disliked ye olde Powerpuff Girls because he saw it a few times and thought it was nothing but feminist propaganda. It was that libel that inspired this post in the first place. I just marathoned the entire thing in order to write an essay about its ethical philosophy, and I can say with confidence that the original series waded into the muddy waters of so-called identity politics (a place it really didn’t belong) only twice in its six-year run. Once, it made fun of masculine posturing in a more-or-less standard “let the girls play too” fashion. Then, in the episode “Equal Fights,” it mocked feminism.

The villainess of “Equal Fights” is a man-hater named Femme Fatale who robs banks but only wants Susan B. Anthony coins because paper bills have men on them (and that’s freaking hilarious). She escapes the two-fisted vigilante justice of the Powerpuff Girls by convincing them that all the men in their lives are oppressing them. The girls turn into man-haters themselves until their schoolteacher and the Mayor’s secretary sit them down and talk sense into them by pointing out that, in fact, all the men they know treat them quite well.

Bet the new version won’t have an episode like that. If it did, the Tumblrinas would be up in arms, and the creators wouldn’t get invited to any more mutual stroking sessions at Huffington Post.

The “Equal Fights” episode ends with an homage to Susan B. Anthony, so it is feminist in a certain sense: it embraces the old feminism of the women’s suffrage movement, but it explicitly rejects Second Wave feminism in the person of Femme Fatale.

Allegra Frank, in the article linked and quoted above, claims the old show is subtly “deconstructive” of commonly accepted notions of girlhood. Even if the series clearly didn’t openly embrace feminism in its current forms, is there merit to Frank’s claim? That’s hard to say, partly because, as with “princess” in the NPR interview, Frank doesn’t say what she means by “deconstruct.” So although I’m not sure I understand the question, my answer is, No.

Bear with me. We can find this in many forms of entertainment, but it appears to me to be most readily visible in cartoons: a certain appeal can be created by presenting the audience with contrasts. The more violent are the contrasts, the more memorable they are. I believe DuckTales, which was big when I was a kid, was popular partly because the cartoonish characters appeared suited for a small, gag-oriented show, but instead went off on big, multi-episode adventures. The character type contrasted violently with the plotlines.

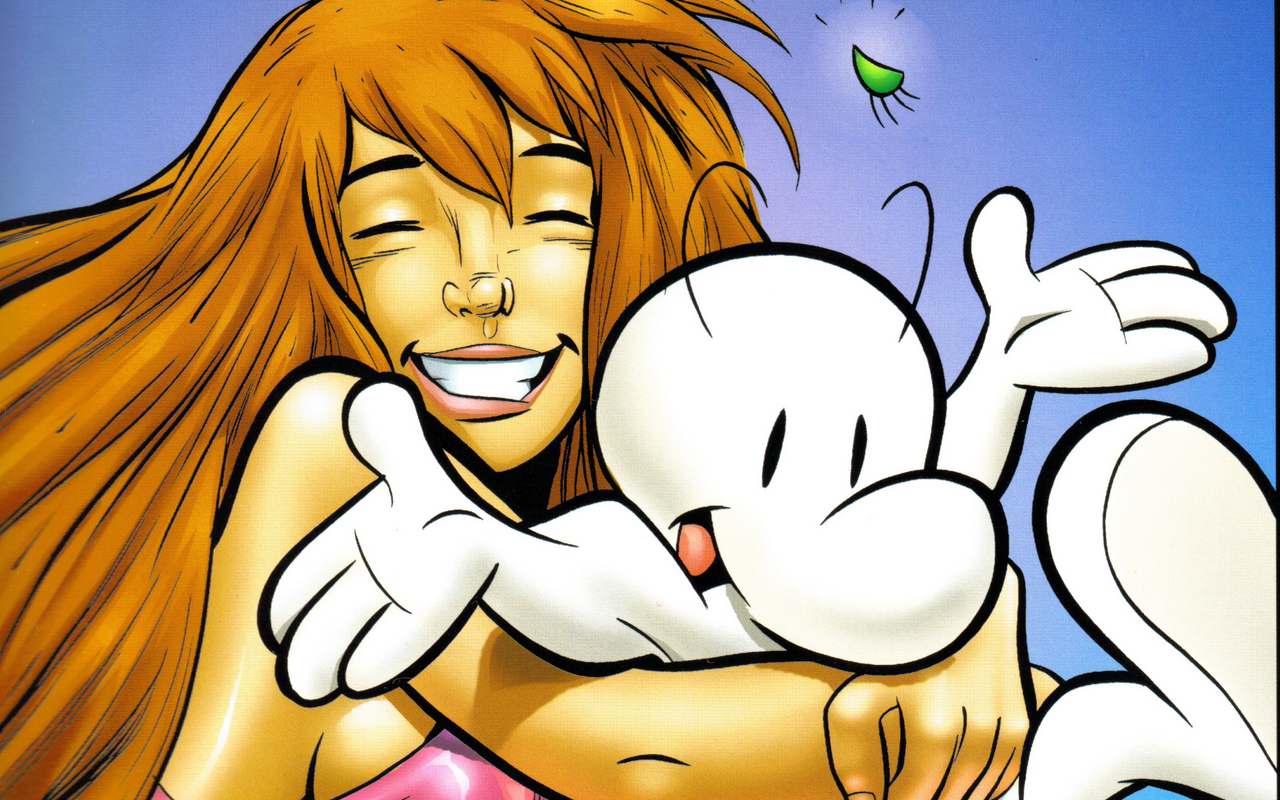

Jeff Smith employed this same contrast effectively in his famous (and timeless) Bone comics. The contrast between the goofy cartoon characters and the sword-and-sorcery adventure they find themselves in extends even to the character designs:

That’s Thorn and Bone, the protagonists from the series. They crackle in every panel they share together, and it’s due in large part to the difference in how they’re drawn.

In The Powerpuff Girls, there is a violent (literally) contrast between what the characters are and what they do. The show effects this contrast by making the characters hyperfeminine (yes, even Buttercup, who’s tomboyish, not mannish) and making them kindergartners.

This is an exaggeration of something we can see in a lot of superhero or magical girl stories, in which the character tries to live a normal life while having an obligation to fight crime, and possibly maintain a secret identity. The Powerpuff Girls don’t “deconstruct” girlhood, but implicitly affirm it: if they were not girls in the conventional sense readily grasped by the audience, the show’s central gimmick would fall apart.

The Powerpuff Girls do not try in any fashion to attack, subvert, or alter their girlhood, but rather wish they could be normal little girls like their classmates. In the episode “Superfriends,” they play in an entirely conventional and girlish fashion with the little girl next door, but must frequently leave in order to fight monsters destroying the city. In the jaw-dropping rock opera episode “See Me, Feel Me, Gnomey,” they are content to lose their powers, pass their responsibilities onto someone else, and “play all day.”

The Powerpuff Girls also had a clear understanding of the differences between boys and girls. Unlike the stupid “Man Boy” from the new series (somebody phoned that one in), the original presented us with the girls’ Rule 63 counterparts, the Rowdyruff Boys. The episodes in which the boys appear are subtle and humorous commentaries on the interactions between little boys and little girls. During their first encounter, the Powerpuff Girls and Rowdyruff Boys wreck much of the city as they punch each other through buildings and throw busses at each other. In spite of the large-scale destruction, the battle has much the character of a playground spat, like boys trying to get the attention of the girls they like by pushing them down and rubbing dirt in their hair. The boys are stronger than the girls are, so the girls fear they can’t overcome them until Miss Sara Bellum gives them a hint. Then they at last defeat the boys, not by using their fists, but by playing kissy-face, which causes the boys to explode from a case of terminal cooties.

When the boys come back for a second round, the villain Him has given them a cootie inoculation, so the girls’ kisses only cause them to grow bigger and stronger. After another rough battle (and the show’s most gag-inducing gross-out jokes), the girls finally win when they realize they can weaken the boys by questioning their masculinity.

Lying under all of this, though hinted only in small ways, are suggestions that the boys and girls on some level actually do like each other. So it’s no surprise that a lot of fans ship it.

Tongue-in-cheek though all of this is, it is a surprisingly complex and, more importantly, true depiction of the dance between male and female. For the most part, boys and girls really are disgusted with each other at a young age, or pretend to be, and prefer the company of their own sex. Those opinions, of course, change as they age, as when the Rowdyruff Boys become immune to cooties and instead come to like getting kisses from the cute girls. And, of course, nothing takes a man apart more effectively than a woman attacking his masculinity, at least if it’s the right woman.

Deconstruct girlhood? It is to laugh. If the show did not have a clear understanding of what girlhood is, it would lose what makes it special and turn to mush. The image of cutesy little girls beating the snot out of a supervillain or kaiju sticks with us and appeals to us exactly because we know that’s not how things usually go. The show rides on the contrast between the cutesiness and the violence.

Although The Powerpuff Girls takes its inspiration from American superheroes, this same basic idea underlies the “magical girl warrior” concept. Naoko Takeuchi dreamed up Sailor Moon right around the same time that Craig McCracken first created his superheroine tots under the ill-advised title of Whoopass Stew (which Cartoon Network wisely changed). Sailor Moon offers the same contrast, in perhaps more exaggerated form: it’s about hyperfeminine girls with superpowers.

Director Kunihiko Ikuhara, who directed much of the Sailor Moon anime and then went on to distill its central conceit in Revolutionary Girl Utena, once said that he believed the popularity of Sailor Moon was due not to the romantic elements, but to the violence, and I believe he’s correct. There is a startling image in both manga and anime that I believe might be almost solely responsible for the huge popularity of the series; it is Sailor Moon’s confrontation with her first monster. At first, the show presents us with a girly heroine who is combination genki girl and crybaby. But then she slices a monster’s head off (in the manga) or confronts a creature that twists its head around backwards Exorcist-style (in the anime). Even when you know it’s coming, it startles. In the same way, the Powerpuff Girls slugging a villain or taking down a monster startles. And that is why they are popular.

For this reason, neither Sailor Moon nor The Powerpuff Girls “deconstructs” notions of girlhood. It simply can’t. These stories are ill-equipped for such a task because, without girlhood, they have nothing on which to base their appeal. Without girlhood, they would be indistinguishable from other superhero shows.

And if the new version really is trying to turn the franchise into a feminist screed, that might explain the negative reviews and bad press. It’s lost sight of its core concept.